Formerly a bohemian, slightly raffish London neighbourhood, it is no exaggeration to say that Chelsea became the fashion capital of the world in the 1960s and the heart of swinging London.

An area that was previously the down-at-heel cousin of respectable Knightsbridge and Belgravia nurtured a fashionable enclave of inspirational clothing boutiques, including Mary Quant’s first shop along King’s Road. It contained the sort of restaurants that were as much about being seen in as eating in, and it had no shortage of high-profile residents. Mick Jagger and Keith Richards, with Marianne Faithfull and Anita Pallenburg respectively, both lived in houses on Cheyne Walk overlooking the Thames; Eric Clapton moved to the neighbourhood in 1968; and the film director Carol Reed lived on the King’s Road.

The district’s name alone had enough prestige to launch a chain of clothing shops, Chelsea Girl, that were a staple of every British high street from the late 1960s onwards – bringing a little of that west London magic to a corner of Cardiff, Dundee or Norwich.

So, it is something of a surprise to find out that Chelsea, synonymous as it is with creatives, the avant-garde and rebels, still has large swathes of its territory under the ownership of one aristocratic family. That family is the Cadogans, now headed by Edward, the 9th Earl of Cadogan. Established in the early 18th century, when the 2nd Baron married Elizabeth Sloane, the daughter of a wealthy landowner, the Cadogan land at its peak covered about 200 acres.

Now it is a ‘mere’ 93 acres but what acres! Radiating out from Sloane Square, it covers much of the famous King’s Road, travels north to the fringes of Hyde Park and Knightsbridge and south towards Pimlico and the Thames. It contains more than 3,000 homes, 300 shops and about 500,000ft2 of office space. Results posted in June placed its value at £5.1bn.

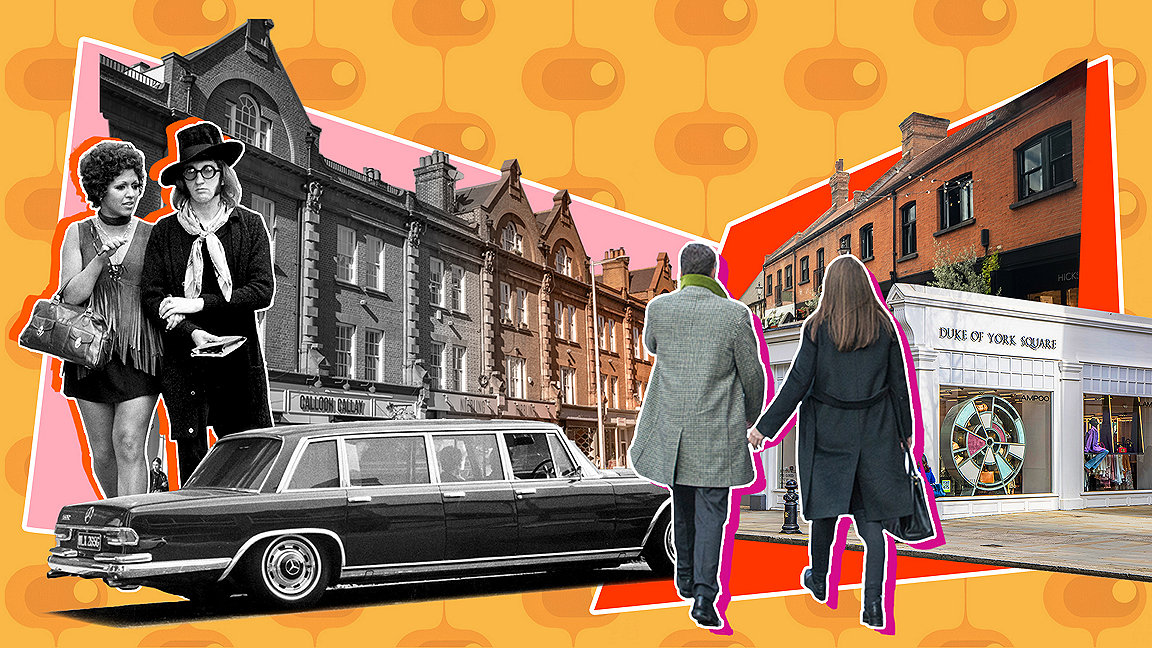

Punks on the King's Road, 1977

“Quite a lot of my job is picking retailers who will fit in and complement us” Luke Hamilton-Jones MRICS, Cadogan Estate

Shops on the King's Road 1969

Luke Hamilton-Jones MRICS, one of Cadogan’s asset managers, insists that, despite its wealth and heritage, the estate is “very lean and has a very flat management structure – I’m on first-name terms with everyone here”.

“Here” is the Cadogan HQ in Duke of York Square, which neatly illustrates the uniqueness of the estate: the offices (built on Cadogan land) are a mix of cool stone floors and plate glass frontage juxtaposed by wood panelled interiors and large portraits of various Cadogan and Sloane ancestors. There are old maps and charts of the Cadogan land and a cabinet containing family mementoes and curiosities such as medals and hand-written letters. Through the window, there is a view of children from a local prep school trotting around the running track at which Roger Bannister used to train – which is also owned by the Cadogan Estate.

Hamilton-Jones’s current beat is Sloane Square and Pavilion Road which runs just off it, behind the Peter Jones department store (another Cadogan asset). Business is ticking along very nicely post-pandemic, he says, but, he’s at pains to point out, it’s not all about bringing in rents. “We allocated about £20m to help our tenants during COVID-19 and now we’ve bounced back quite quickly. We’re getting four or five bids for every retail unit, we have a very vibrant area.”

Part of this vibrancy is, he feels, the way in which Cadogan operates its portfolio. “Everything looks very organic but it’s about how it’s made to be. It’s hugely curated.” He grimaces at the word and promptly apologises for appearing pretentious. “Quite a lot of my job is picking retailers who will fit in and complement us. The pitch for the second-hand shop [luxury pre-owned store Lampoo] was that circularity and sustainability are vital for the future and it’s something slightly different. We’re always looking to what’s next.”

“We allocated about £20m to help our tenants during COVID-19 and now we’ve bounced back quite quickly” Luke Hamilton-Jones MRICS, Cadogan Estate

Pavilion Road, 2022

These small swerves away from the expected path come down to a freedom that few other property businesses enjoy. The estate’s hereditary wealth means it can afford to be more creative and not solely profit-driven in its decision-making. It has, for example, championed new businesses by encouraging pop-up shops (temporary leases often at discounted rents) which have allowed them to experiment and find a foothold in the area.

“Coming out of COVID-19, we brought in some pop-up shops. Jam Industries [a clothing company owned by two brothers] took one of them and now has a permanent lease on King’s Road. It’s one where you walk in and you feel like you’ve done something good which is quite difficult in [corporate] property.”

Although he no longer works directly with the King’s Road, Hamilton-Jones has a proprietorial interest in it still, pointing out shops that he is particularly proud of such as Rixo – another former pop-up – and Ganni, the hot Danish brand that, he says, was part of a strategy to attract other fashion stores.

But his real love is Pavilion Road, formerly a drab collection of garages and storerooms tucked away behind the Peter Jones department store. It is a little ridiculous to think of any part of Chelsea having been recently gentrified – it is regularly named among the UK’s wealthiest boroughs – but Pavilion Road really has transformed in the past few years. It now looks as if the film director Richard Curtis (Notting Hill, Love Actually) has left behind romcoms and gone into town planning. Bathed in the sunlight of a bright summer’s day, part of the street is pedestrianised and sprinkled with outdoor tables and planters, while up above the diners and shoppers flutter strings of Union Jack bunting. Here, the estate has created the ideal high street – a butcher, a baker, and an ice-cream maker as well as a stationery shop, a florist, a cheesemonger.

“We wanted slow retail in this area, a selection of interesting, fascinating things,” says Hamilton-Jones. “We went to the local community and they said they wanted shops where they could get a newspaper and a pint of milk. What I love about Pavilion Road is that it shouldn’t be signposted, it almost shouldn’t be known about.”

But even on Sloane Street – probably the ritziest part of the Cadogan portfolio – where there are shops leased to Gucci, Prada, Chanel and Bottega Veneta, he points to an ongoing Cadogan project, the upgrading of the pavements. “It’s part of our public realm scheme,” he says. “We plan to improve almost everything the eye sees, including pavements, lighting and most importantly create a beautiful green boulevard from Knightsbridge to Sloane Square.” Working in partnership with the local authority, this will cost Cadogan about £46m but Hamilton-Jones insists that “if we invest the money now, it lasts for decades. It will change how Sloane Street works.”

The King's Road, 1973 and 2022

Like many asset managers, he is having to deal with all kinds of upgrades – some less glamorous than others. As legislative demands on sustainability become ever tighter, Cadogan finds itself in the position of holding a raft of older, quirkier and often protected buildings that need to be brought into line with energy efficiency standards that their builders could never have envisaged. The large (single-glazed) windows and (cavity-less) brick walls give the area its period charm but are, of course, a nightmare to make greener.

“Pretty much every decision we take now has an element of sustainability in it,” says Hamilton-Jones, nodding towards a terrace of shops and apartments opposite Duke of York Square which has been discreetly retrofitted. “It’s a question of looking at what we can do. By 2030, our buildings may have to have an EPC of B. That’s the most exciting bit of the work, seeing how we can make the business more energy efficient.”

He insists that he loves the challenges that these directives create but the real beauty of his job seems to be its immediacy. “I’m a 12-minute walk away from my furthest property and that makes everything so much simpler. I’m rarely fighting fires because the fire doesn’t get started, I can go and have a chat with tenants,” he says. “Ultimately we’re a property company but also part of the community.”

Duke of York Square, 2023